Mount Everest - named for a paragon of surveying

Did you know that the highest mountain in the world is named for a surveyor who never laid eyes on it?

George Everest was the Surveyor General of India from 1830-1843, during the time when Great Britain was consolidating its control over the country in order to have full access to its vast resources. His work was so important to the fulfillment of that goal that the mountain was eventually named after him – despite his protests.

The early years

Everest was born in 1790 in Wales, the eldest son and third of six children born to Lucetta Mary and William Tristram Everest. His father was a lawyer and justice of the peace and owned a large estate in south Wales.

He received his early schooling at the Royal Military College in Marlow, Buckinhamshire. This school educated future military officers who were essential in establishing and holding the far-flung colonies of the British Empire. By the time Everest was 16, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Bengal Artillery and sailed for India in 1806.

Very little is known about his earliest years in India, but sources note that young Everest was very keen to learn. One of his first acts after reaching India was to seek out teachers of the local languages to achieve reasonable fluency. After this, he found some mathematical and astronomical textbooks and taught himself these subjects to a very high level. This ability to learn on his own proved to be an essential skill throughout his life.

He had the opportunity to develop his math, astronomy and surveying skills when he was transferred to Java during a brief period when the island was controlled by the British. In 1815 Lt. Everest was appointed by Lieutenant-Governor Stamford Raffles to complete a survey of the island.

To do the survey, Everest had to purchase his own equipment, so he only had a simple form of theodolite to use. It seemed to do the job, because he was able to survey the island, concentrating on militarily strategic areas including mountains, harbors, communication routes and near-shore waters. Everest arrived back in India in late November 1816.

Just a few months later, he was called on to survey land that would be traversed by a telegraph line stretching 400 miles west from Calcutta. He only got halfway through that project when he learned of his appointment as Chief Assistant to Col. William Lambton for the Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS).

The Great Trigonometrical Survey

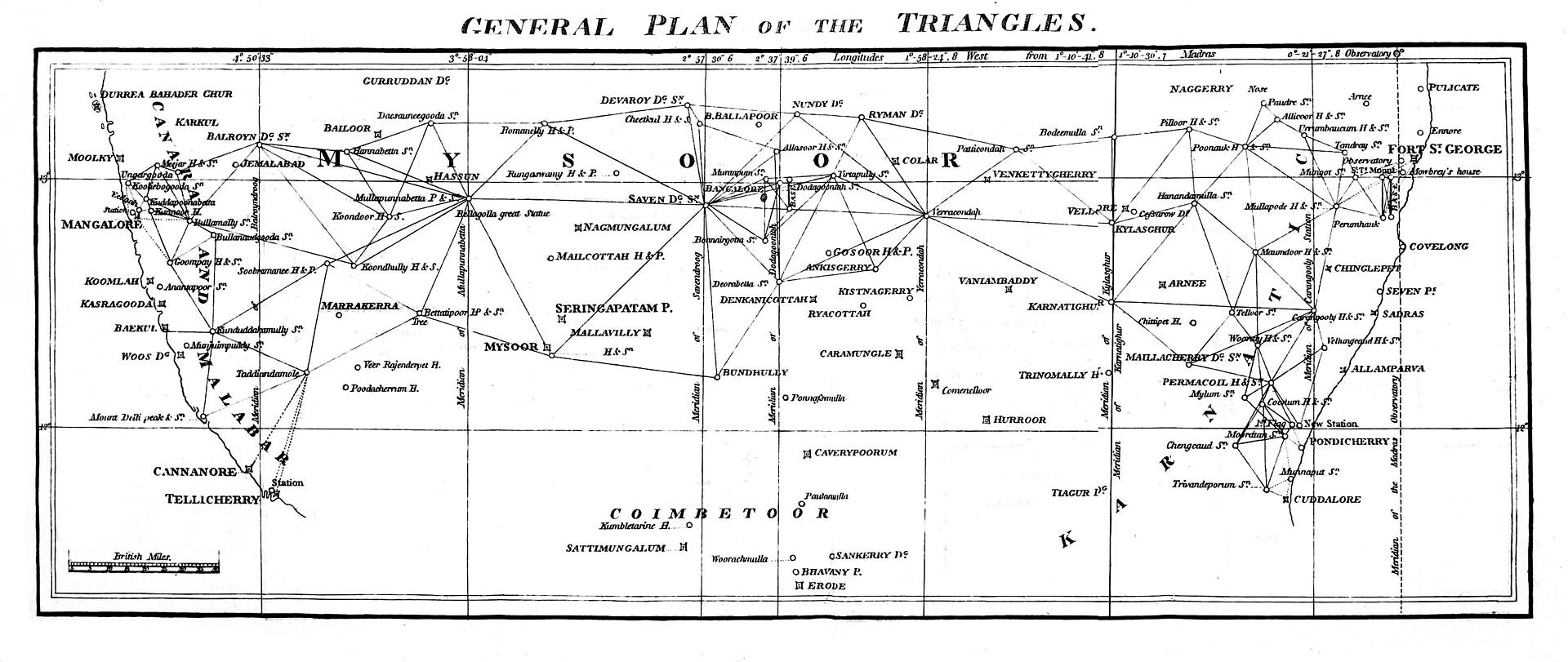

The Great Trigonometrical Survey was a geodetic survey (triangulation survey equipped with theodolites). The GTS originally began in 1802 with the measurement of a baseline near Madras. Major Lambton selected the flat plains with St. Thomas Mount at the north end and Perumbauk hill at the southern end. The baseline was 7.5 miles long. Later, high vantage points were established on the hills of the west so that the coastal points of Tellicherry and Cannanore could be connected. The distance from coast to coast was 360 miles (580 km) and this survey line was completed in 1806.

The East India Company thought that this project would take about five years, but it took nearly 70 years. Because of the extent of the land to be surveyed, the surveyors did not triangulate the whole of India but instead created what they called a "gridiron" of triangulation chains running from north to south and east to west. At times the survey party numbered 700 people. The GTS was conducted independently of other surveys, notably the topographical and revenue surveys.

Everest joined Lambton on January 8, 1819 and the two of them observed some of the Arc stations near Bidar.

Everest was responsible for surveying the meridian arc (the curve between two points on the Earth’s surface which have the same longitude) from the southernmost point of India to Nepal. The distance to be measured was spread across 1500 miles and took 35 years to complete.

In the thick of it

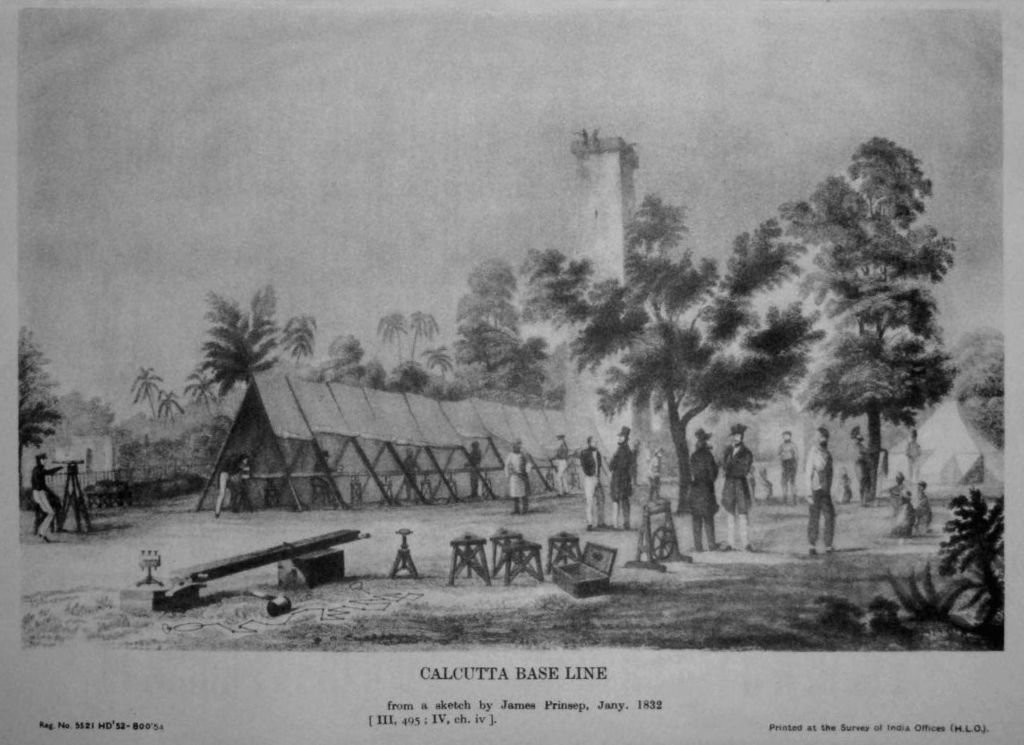

Great Trigonometrical Survey measurement of the Calcutta baseline in 1832 by George Everest. The engraving is based on a sketch by James Prinsep. It shows a Ramsden chain being set on coffers supported by pickets. The tent is to avoid expansion due to heat. The boning telescope is used to align the links of the chain.

Everest began the work of surveying the meridian arc northward from Cape Commorin in one of the worst parts of the country as far as health, vegetation, and climate was concerned.

By July, Everest was in the middle of the Indian jungle between the Godavari and Kristna rivers with a team of 150 men. These jungles were home to wild boars, tigers, snakes, bird-sized spiders, stinging insects, leeches and disease.

Unfortunately, it was monsoon season and within a few weeks, Everest and his whole party had succumbed to malaria. They had to give up the survey and returned to Hyderabad to recover. Ten percent of his men died on this first attempt.

Everest tried to continue the next year, but within weeks he was again struck down with malaria. On October 1, 1820 he sailed to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to recuperate.

Everest was plagued by fever for the next few years and was forced to return to England in 1825 to recuperate.

Recuperation

While in England, Everest spent five years improving his instruments. He worked with a London instrument maker to develop a smaller, lighter and cheaper theodolite. He also tested using compensation bars to measure distance. These bars are simply two bars strapped together – one made of iron and the other of brass that expand to different, specific degrees when heated. This compensates for the effect of temperature on distance measurements. He also settled on a new surveying strategy. Rather than covering the whole country with triangles, he would create a gridiron pattern: an array of north-south and east-west traverses across the country that intersected at right angles.

In 1830, Everest returned to India to try to complete the survey. He started by triangulating from Dehra Dun to Sironj, a distance of 400 miles across the plains of northern India. The land was so flat that Everest had to design and construct 50 foot high masonry towers on which to mount his theodolites. Sometimes the air was too hazy to make measurements during the day so Everest had the idea of using powerful lanterns, which were visible from 30 miles away, for surveying by night. To do this work, Everest now had 700 men, as well as four elephants for the principals to ride on, thirty horses for the military officers and forty-two camels for carrying supplies.

Index to the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India (1922). India is shown on a 1-degree grid of green lines. The blue triangles indicate the Great Trigonometrical w:triangulation measurements. Triangulation series are indicated by a number in parentheses. These series are described in the table at the bottom left. The red dash-dot lines are telegraph longitude area. Among the many accomplishments of the Survey were the demarcation of the British territories in India and the measurement of the height of the Himalayan giants: Everest, K2, and Kanchenjunga.

By the time Everest retired from the survey in 1843 most of the job was done. The survey’s line of triangles up the spine of India covered an area of 56,997 square miles, from Cape Comorin in the south to the Himalayas in the north. What is utterly remarkable is the accuracy they achieved. From time to time, they would measure the length of a baseline at the far end of a line of triangles to check their results. One such measurement of a 7.19 mile baseline differed only 3.7 inches from the value calculated by triangulation.*

But how did Mount Everest get its name?

Mount Everest

It was Everest’s successor, Andrew Waugh, who extended the triangulation network into the Himalayas and named the mountain after him. Waugh wanted “to perpetuate the memory of that illustrious master of geographical research…Everest.”

It was likely that Waugh wasn’t aware of the local Tibetan name for Mount Everest: Chomolungma. At the time it was identified as the highest peak, foreigners were not allowed in Nepal or Tibet, so the name was unknown.

In 1856, Waugh wrote to the Royal Geographical Society, saying, “I was taught by my respected chief and predecessor, Colonel Sir George Everest to assign to every geographical object its true local or native appellation. But here is a mountain, most probably the highest in the world, without any local name that we can discover, whose native appellation, if it has any, will not very likely be ascertained before we are allowed to penetrate into Nepal.”**

However, “Everest objected that the Himalayan peaks should retain their local names. He also protested that “the native of India” could not pronounce his name, nor could it be written in the local Devnagari script. Nevertheless, Waugh ultimately prevailed. In 1865 the Royal Geographical Society named Peak XV after the man who had been responsible for framing the subcontinent with a gridiron of triangles and whose careful and persistent geodetic survey had established a modern foundation for measuring elevations across the Indian landscape, including the Himalayas.” ***

Everest died in London in 1866 at age 76, shortly after the world’s highest peak was named after him. It’s unlikely that many people would know anything about the amazing surveying work of George Everest if Peak XV had not been named after him.

Fortunately, surveyors now have amazing technologies and accessories that make surveying easier and even more precise than in Everest’s day. Count on Berntsen to help you with the mountain of work that lies ahead of you!

Sources:

https://powersuk.com/george-everest/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Everest

https://mycoordinates.org/history-jim-smith-6/

http://scihi.org/george-everest/

https://alpinedrome.wordpress.com/tag/the-great-trigonometrical-survey-of-india/

https://www.bluesci.co.uk/posts/history-the-great-trigonometrical-survey